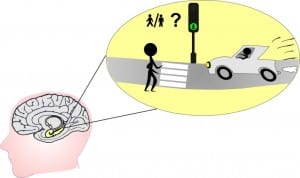

The process by which situational awareness is formed begins with using your five senses (seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and smelling) to gather information from your environment. That may arguably be the easiest part of the situational awareness developmental process so long as you are “paying attention” to your environment. Once the senses gather information, it converts it into an electrical code that crackles its way down neural pathways to various destinations.

The process by which situational awareness is formed begins with using your five senses (seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and smelling) to gather information from your environment. That may arguably be the easiest part of the situational awareness developmental process so long as you are “paying attention” to your environment. Once the senses gather information, it converts it into an electrical code that crackles its way down neural pathways to various destinations.

At some point, the inputs from the senses must be combined, compared and contrasted to help achieve a coherent understanding of what is happening. This “understanding” is the second step along the way to developing situational awareness. But it’s not always easy to understand the meaning of information, especially when there is conflict among the inputs.

Conflict

So long as the inputs from the five senses are congruent – or compatible – then it can create a quick and relatively easy process to achieve understanding. But, alas, this is not always the case. Each sense gathers information in a unique way and independent of the others. The senses often do capture their information at the same time, however, and this can be helpful when the inputs that are being processed are compatible. The process by which the inputs are aligned is known as sensory integration.

While each of your senses gathers information independently, the senses rely on each other to confirm or refute each other. I am reminded of one of my kids’ most favorite grade school science fair projects. Blindfold a person and ask them to smell and/or taste various foods. Without the blindfold on, participants have the opportunity to employ sensory integration. This, in turn, triggers anticipation.

While each of your senses gathers information independently, the senses rely on each other to confirm or refute each other. I am reminded of one of my kids’ most favorite grade school science fair projects. Blindfold a person and ask them to smell and/or taste various foods. Without the blindfold on, participants have the opportunity to employ sensory integration. This, in turn, triggers anticipation.

For example, without a blindfold on, give a person some peanut butter on a spoon. As you take the jar of peanut butter (which is in clear view of the participant) and unscrew the lid, anticipation is already engaging. If the participant likes the taste of peanut butter their mouth may begin to water. As you dip the spoon into the jar the participant may smell the peanut butter which furthers their anticipation. The eyes and nose tell the brain (and taste buds) what’s coming in advance of the arrival. When the peanut butter hits the tongue, Nirvana is achieved!

But, what happens when the senses are not permitted to integrate? Using the same taste experiment, start with the participant blindfolded and without having known that peanut butter was going to be the test food. Without visual input there is no anticipation. Keep the jar of peanut butter far enough from the participant that they are not able to smell its peanutiful goodness. Again with no input from smell there will be no anticipation. Finally (and this is the really sinister part of the experiment) use a small amount of water to thin out (change the pasty consistence) of the peanut butter so it takes on the consistency of a liquid instead of a paste. This robs the participant of the sensory input, the feel of peanut butter in the mouth (which, by most people’s account has a distinctive thick pasty feeling in the mouth).

But, what happens when the senses are not permitted to integrate? Using the same taste experiment, start with the participant blindfolded and without having known that peanut butter was going to be the test food. Without visual input there is no anticipation. Keep the jar of peanut butter far enough from the participant that they are not able to smell its peanutiful goodness. Again with no input from smell there will be no anticipation. Finally (and this is the really sinister part of the experiment) use a small amount of water to thin out (change the pasty consistence) of the peanut butter so it takes on the consistency of a liquid instead of a paste. This robs the participant of the sensory input, the feel of peanut butter in the mouth (which, by most people’s account has a distinctive thick pasty feeling in the mouth).

And what will the results be? The participant may not be able to identify the flavor. Some may say it tastes “nutty” and some may describe it as tasting like some sort of meat. And, of course, there will be some who can still identify it as peanut butter. But what is indisputable is the amount of brain power needed to assess and analyze this flavor will be substantially greater because of the lack of multiple sensory inputs.

Confusion

The senses can also send conflicting and confusing messages. We can demonstrate this with another taste and smell experiment. This one doesn’t involve food. Rather, it involves foaming hand soap. Some of those soaps have amazing aromas. My favorite scented soaps are strawberry and apple.

For this experiment, let’s use strawberry. Blindfold a participant. Tell them you are going to have them taste a small, red fruit. First, have them smell the soap. You may have to spread some on your hands and hold them close to their nose.

Ask them, based on the smell to tell you what the fruit is. If they do not guess right, give them some hints, but do not tell them it’s strawberry. Make them guess the right answer. Once they have guessed “strawberry” correctly, have them taste the soap.

Ask them, based on the smell to tell you what the fruit is. If they do not guess right, give them some hints, but do not tell them it’s strawberry. Make them guess the right answer. Once they have guessed “strawberry” correctly, have them taste the soap.

Their reaction will provide quick and evident proof of sensory conflict and confusion. The participant may even become a bit upset (so be sure to do this experiment with someone you know will not react in a harmful way toward you… or make sure it’s someone you can outrun).

There is the proof. The senses can be in conflict and this can create confusion. And where there is confusion, situational awareness can erode. At the very least it can require a significant amount of brain power to resolve the conflict at the participant in the latter taste example exclaims “What the heck was that?!?!”

Domination

As I am explaining the process of sensory integration in my Flawed Situational Awareness programs I often get asked if there is a conflict between senses, is there any one sense that dominates the others? The answer can be complicated because there are some variables (e.g., emotions… which I will discuss in a moment).

All other variables being equal, the visual input will dominate. The visual processor in the brain is larger than all the other sensory processors combined. It makes sense that during the process of evolving into the human species, visual processing would be critically important to survival.

All other variables being equal, the visual input will dominate. The visual processor in the brain is larger than all the other sensory processors combined. It makes sense that during the process of evolving into the human species, visual processing would be critically important to survival.

Of course, we already know that vision is the dominant sense. We even have a cliché to remind us. “Seeing… Is… Believing!” The problem is, simply because any one sense may win out over another, it doesn’t mean that sense is most accurately depicting reality.

Emotions

Notwithstanding the dominance of visual processing, emotions also play an important role in information processing domination. Emotions aid in memory formation and memory recall – both important components in the situational awareness formation process. The more emotional the input, the more likely it may dominate the process toward understanding.

Take, for example, two words. Mayflower and Mayday. These two words should evoke very different emotional responses, especially in first responders. The former may evoke memories of pilgrims and Thanksgiving. The latter may evoke memories of Mayday training, firefighter fatalities and funerals.

Not withstanding the role that context and environment play in understanding, you’re far more likely to turn your attention to the words that follow “mayday” than the words that follow “mayflower.”

Dr. Gasaway’s Advice

Like so many of the barriers that can erode your situational awareness, it is far easier to explain how and why sensory conflict and confusion occurs than it is to give you tangible advice about how to resolve the conflict and confusion.

Like so many of the barriers that can erode your situational awareness, it is far easier to explain how and why sensory conflict and confusion occurs than it is to give you tangible advice about how to resolve the conflict and confusion.

When you experience sensory conflict you may, as in the case of the strawberry hand soap experiment, realize it immediately. The subject of your experiment may not know instantly that the foul taste is hand soap, but they’ll certainly, and immediately, know it was not strawberries.

Then, the investigative process begins as your participant gathers more information to help explain (and resolve) the conflict. Occasionally, the jolt of confusion will be so pervasive that you immediately deploy other senses to aid in understanding. For example, it would be a natural and anticipated reaction that when the participant expected to taste strawberries and, instead, tasted hand soap, they would immediately remove the blindfold in an effort to gather visual information about what they just tasted.

Here are some strategies you can deploy to help manage situational awareness issues related to sensory conflict:

Be vigilant to the fact that your perception of reality may not always be true reality.

Be mindful that what you see, hear, feel, taste and/or smell is not always accurately understood in your brain.

Be accepting of the fact that simply because one sense may dominate another, it does not mean that sense is more accurate.

Finally, when you are operating in an environment where there is massive amounts of input to any one sense (e.g., an environment with lots of radio traffic), your brain can lock on to that sense. If this happens, that sense can not only control your understanding, but it can also turn off the processing of other sensory inputs.

What does that mean for you? Simply this: When you are in an environment with massive amounts of auditory input (be that talking, radios or simply noise) it can be harder to understand what you are seeing. Conversely, when you are operating with massive amounts of visual inputs it can be harder to understand what you are hearing.

This is why we sometimes, reflexively, close our eyes when we are listening or seek refuge to a quiet place when we are trying to process complex and detailed visual inputs.

Action Items

1. Share and discuss an example where someone was confused on an emergency scene because there was a conflict between sensory inputs (for example audible and visual information).

1. Share and discuss an example where someone was confused on an emergency scene because there was a conflict between sensory inputs (for example audible and visual information).

2. Discuss how the example above was resolved.

3. Discuss strategies you can deploy to help manage sensory conflict.

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

SAMatters Online Academy

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

Twitter: @SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

Instagram: sa_matters

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters Radio

iHeart Radio: SAMatters Radio

Pingback: Avizem znaki - Kako otroku pomagati? Reha Medical.si